Mind in Two Tongues: Psychological Insights into Bilingualism and Language Learning

Introduction – Opening the Bilingual Mind

Bilingualism is more than the ability to communicate in two languages—it reflects a dynamic interplay between linguistic systems and cognitive processes. The bilingual brain engages in constant simultaneous activation of languages, managing competition between them through mechanisms such as language switching and inhibitory control. These mental operations shape not only language processing but also broader cognitive capacities like attention, memory, and problem-solving. Understanding the psychology of bilingualism sheds light on how learning and using multiple languages can alter brain function and contribute to personal, academic, and social development.

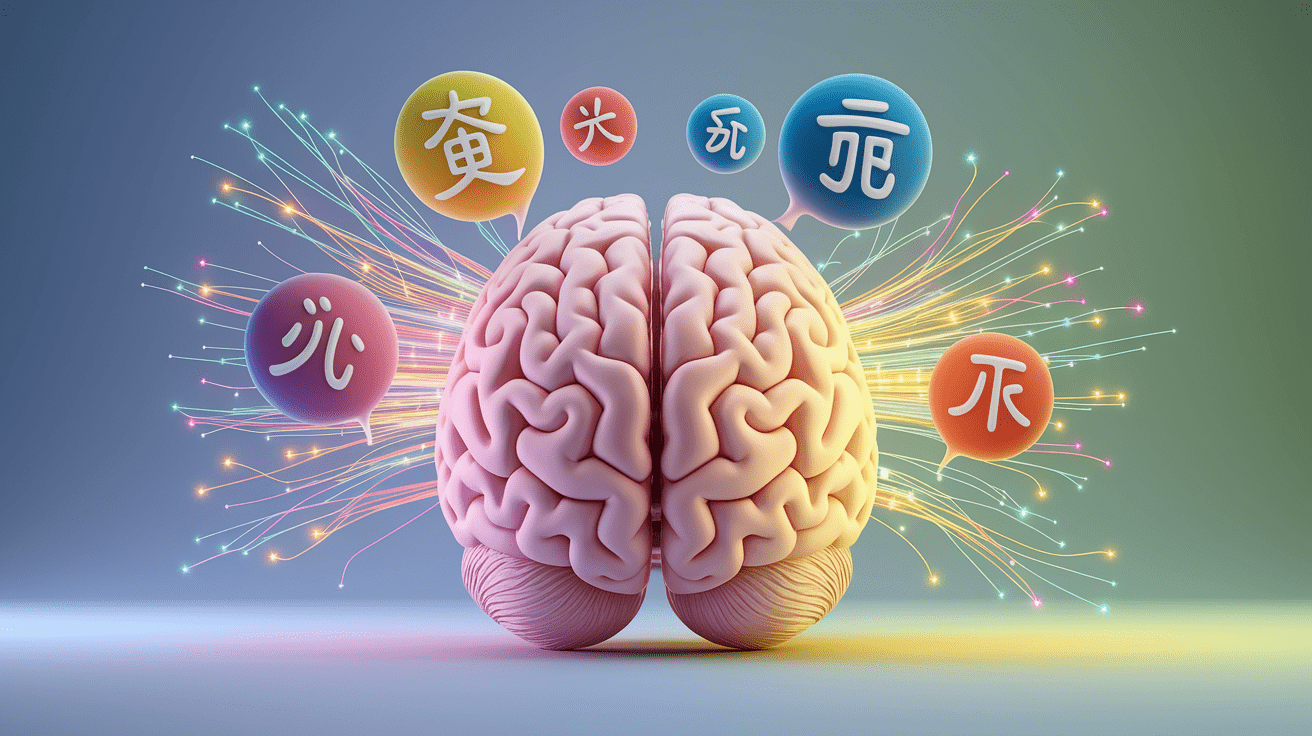

Neural Foundations of Bilingualism

From a neurological perspective, bilingualism requires robust networks for language processing and cognitive control. Neuroimaging research shows that both language systems remain active, even when one is not in use. This activity prompts continuous selection between competing linguistic inputs—a process demanding inhibitory control and attention regulation.

These functions are associated with brain regions such as the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and left inferior parietal lobe. These areas support executive function and facilitate language switching while mitigating language interference during communication. Functional adaptations emerge whether the second language is acquired early in life (simultaneous bilingualism) or later (sequential bilingualism), though proficiency strongly influences these neural responses.

Neuroplasticity Through Language Learning

Structural brain changes observed in bilinguals highlight the role of neural plasticity in second language acquisition. Studies report increases in grey matter density and improved white matter connectivity in regions linked to working memory, phonological processing, and semantic memory. Even brief periods of formal instruction can produce detectable changes, which become more pronounced with sustained language practice and higher proficiency levels.

- Grey Matter Density: Enhanced in the left inferior parietal region, supporting vocabulary acquisition and multilingual processing.

- White Matter Integrity: Increased efficiency in connections between language-related brain regions, contributing to faster retrieval and reduced cognitive load.

- Wider Cognitive Impact: These physical changes extend to non-verbal tasks, boosting cognitive flexibility and problem-solving ability.

Cognitive Advantages Beyond Words

The cognitive benefits of bilingualism extend well beyond linguistic performance. Managing two active languages strengthens executive functions, such as task switching, attention control, and inhibitory regulation. These abilities are central to how bilinguals navigate language interference and code-switching.

Research indicates that bilinguals often outperform monolinguals in tasks requiring selective attention and rapid adaptation to new rules. Moreover, long-term bilingualism has been associated with delayed onset of age-related cognitive decline, offering protective effects for older adults through sustained cognitive engagement (Kroll et al., 2014).

Literacy and Dual Language Development

Bilingualism influences literacy acquisition through the organization and integration of neural networks. Early biliterates who acquire reading and writing skills in both languages demonstrate more interconnected systems for processing written language compared to those who learn literacy in a second language later.

According to the Common Underlying Proficiency (CUP) model, certain cognitive and linguistic skills—such as phonological processing or metalinguistic awareness—are transferable across languages, enhancing reading comprehension and writing abilities. Nevertheless, proficiency, language dominance, and orthographic differences between languages (e.g., alphabetic vs. logographic scripts) can influence the ease of transferring literacy skills.

Defining Bilingualism on a Spectrum

Defining who is “truly” bilingual is complex. Research on perceptions of bilingualism emphasizes factors such as frequency of language use, context, literacy, and functional ability. For instance, a heritage language speaker with receptive skills but limited production may be perceived differently from a balanced bilingual fluent in both oral and written forms.

These factors highlight that bilingualism exists on a spectrum encompassing additive bilingualism (gaining a second language without losing the first) and subtractive bilingualism (where one language gradually replaces another). Such variability underscores the importance of considering sociocultural and personal identity dimensions in the psychological study of bilingualism.

Applying Psychology to Language Learning Strategies

The psychology of bilingualism offers practical insights for language learning strategies. An interdisciplinary approach incorporating cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and linguistics has led to several effective principles:

- Leverage Inhibitory Control: Practice tasks that require rapid switching between languages to strengthen attention control.

- Enhance Metalinguistic Awareness: Compare grammar, phonology, and semantics across languages to deepen understanding and promote cross-linguistic influence in a positive way.

- Use Immersion and Contextual Learning: Engage in authentic social interactions to lower language anxiety and facilitate vocabulary retention.

- Maintain Heritage Language Skills: Preserve identity and broaden cognitive benefits by practicing reading and speaking in both languages regularly.

- Adapt to Critical Period Sensitivities: For adult learners, focus on neuroplasticity through repetition, multimodal learning, and active communication rather than relying on innate phonetic aptitude.

Conclusion – Tying Tongues and Thoughts Together

The psychology of bilingualism reveals an intricate link between language and cognition. From the constant interplay of two linguistic systems in the bilingual brain to the structural changes brought by language learning, research underscores the mutual reinforcement between language proficiency and cognitive skills. Recognizing bilingualism as a spectrum informed by context, identity, and usage patterns allows for a more comprehensive understanding of its benefits. These insights not only advance academic study but also guide practical strategies for fostering multilingualism in diverse social and educational settings.